For

most of my life I thought miracles were just ancient stories that had probably been recorded by the credulous. But now I’ve changed my mind. For the past five months I’ve

had pronounced breathing problems and I’d been sent by a lung specialist for a

series of tests. The last of these was a video fluoroscopy (an X Ray video); an

odd experience, since you can see your lungs working in almost real time as the images

are projected onto a screen in front of you. The report was brief and clear, I

had a partially paralysed left diaphragm. It was a terrible shock.

A

paralysed diaphragm is the result of damage to the phrenic nerve, the doctor

explained. How did I get it? Probably during my major surgery in 2011 which

opened up my chest to remove a tumour that had grown into my vena cava. The

phrenic nerve runs from your neck around your heart and into your diaphragm.

Apparently such paralysis is a reasonably common side-effect of cardiac

surgery. These things happen, said the doctor. The nerve had been damaged and

my diaphragm was raised and weakly flickering, allowing my stomach to move up and

become wedged inside my ribcage; together these were putting pressure on my

left lung and greatly limiting my breathing. And what could be done about it?

Nothing much, I was told. It was a permanent impairment.

On

top of the shock was fear. I’d had breathing and digestive problems ever since

the surgery in 2011. After a series of tests three years ago, I was told that I

had a hernia in my diaphragm and that this could be repaired by surgery. Still

recovering from the first operation, I wasn’t keen for further surgery so it

was agreed that I would have the remedial operation if my symptoms worsened. Over

time I learnt to live with these problems. In January my breathing had

deteriorated so much that I told my GP I wanted to go back and have the

surgery. But now I was being told that this longstanding diagnosis was wrong

and there could be no surgical solution to the problem. So did this mean that I

was now moving inexorably to ever greater breathing impairment?

On

top of the fear came anger. A moment’s carelessness by a doctor had left me

with a lifetime of problems, which couldn’t get any better and may well get a

lot worse. On top of that, when I had complained about post-surgical problems I

was given the wrong diagnosis. If I’d been given the correct diagnosis three

years ago, then perhaps something could have been done to slow down the

deterioration in my breathing. I was full of questions. The GP couldn’t help me

with any of them. I wrote them all down in a letter to the lung specialist

asking to be seen urgently.

On

top of the anger came depression. I tried doing breathing exercises I found on

the internet but these irritated my already inflamed lungs. The stress on my

lungs had given me asthma too. I felt I was in a downward spiral. Walking and

cycling in the great outdoors had been such a big part of my life; I would have

to face up to letting go of them. I began to imagine myself housebound with an

oxygen tank as my constant companion.

In

truth these were not separate phases but all mixed up together. Each day became

a real struggle. I found myself getting very frustrated and reacting to

irritations that I would previously have brushed off. With no response from the

specialist to my urgent request, I decided to explore other options. I had been

to an osteopath in Holywood who was trained in Eastern medicine and

acupuncture, I booked an appointment.

Ralph

McCutcheon listened to my story and asked me to lie on the treatment table. He

got me to open my mouth and pressed his thumb hard into the roof of my mouth

telling me to breathe deeply at the same time. Next he worked on vertebrae in

my neck and back. Lastly he manipulated my abdomen at the bottom of my ribcage

for a while. That’s fixed it, he said.

I

left the treatment room and did some breathing exercises. There was an unusual

ache in my left side. I thought it was due to his pressure. But the ache

persisted and later I had more feeling at the base of my ribs where my left

diaphragm should be. That evening, my breathing seemed easier. I began to hope

that he had made a difference. I spent an anxious night. On waking I tried the

breathing exercise and felt the left diaphragm flex. It got sore quickly but my

diaphragm seemed to be working much better than before; I could fill my lungs

and breathe more clearly. And my stomach and digestion felt better too; instead

of feeling bloated after eating just a little, I felt hungry and was able to

eat heartily without stomach ache.

It

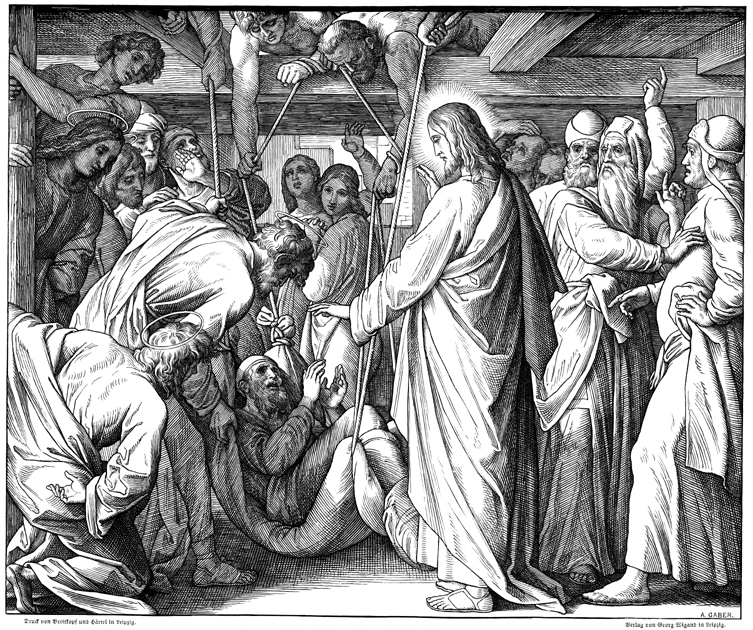

was miraculous. I’d been told by conventional medicine that there was no hope.

I’d been given the laying on of hands. And I seemed to be cured. Thanks to the

blessed Ralph I have a new lease of life.